The medina of Tunis, a labyrinthine ancient city of tiny pathways, cobbled alleys and glorious mosques, dates back to the 13th century and is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. On sunny days, light bounces off the stone white walls, highlighting the bushes of bougainvillea nearby. The souk that’s hidden within the medina’s walls is enormous, brimming with stalls that sell everything from traditional orange blossom perfume to leather bags, round felt hats and stacks of sunglasses. Yet most visitors only make it as far as the souk, missing the mosques, alleys and ancient houses that surround it.

Djamila Binous, a well-known Tunisian historian, wanted to change that. So she launched three-hour group tours of the medina, held on a weekly basis. “I want tourists to be able to discover the old city,” she told us, as we joined her on one of the regular Saturday morning tours. “There are so many hidden gems inside the medina. They should be seen.”

Our tour kicks off at the Mosque of the Kasbah, one of Tunisia’s most famous holy sites. Built between 1231 and 1235 under the ruling dynasty of Abu Zakariya Yahya, the mosque sits on the edge of the medina at the famous Place de la Kasbah, the then-seat of government. The minaret is gold and white, with a shapely gold crown that extends up into the blue Tunisian sky. Binous points out the marble columns and the Ottoman architecture, some of which was renovated after construction. We’re unable to enter the interior, so we head off to a second, smaller mosque that Binous assures us we’ll be able to access.

“Often, the tomb of the mosque’s founder is built into the main building,” she says, as we approach. “This meant a lot of forward planning. The founder had to decide where exactly he wanted to be entombed while he planned the construction of the mosque.” We enter a side study room, adorned with delicate white friezes and a spectacular curved ceiling. Binous explains that many of the study rooms have now been transformed into libraries or even film clubs, as a way of encouraging young Tunisians to engage with the past — and the future — of the ancient buildings. In the central courtyard, an artist’s exhibition is on display; the bright, vibrant paintings contrast with the delicate old architecture. The scent of rose and sandalwood oils hangs heavy in the air as Binous points out the traditional blue-and-white ceramics that border the room.

Our next stop is Rue Sidi Ben Arous, a gorgeous ancient alleyway that is now the subject of a regeneration scheme. Everything is bright and gleaming here; the doors have been painted in shades of yellow, blue and red, and the old dars (traditional courtyard houses) are being transformed into upmarket restaurants, ice cream bars and cafes. Archways are iced with taupe brick and petals of jasmine flutter onto the cobbled path. We make a stop at the hip new cafe La Parenthese, which has reams of history hidden within its walls. The owners explain that while renovating the building, they found an ancient byzantine column; it is proudly on display inside the ladies’ room.

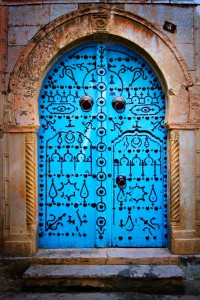

Next door to La Parenthese is Dar El Medina, a restaurant and boutique hotel inside a typical medina house, or dar. Binous explains that according to the traditional construction of dars, rooms were of equal size and resembled a T-shape. The hotel has a stunning whitewashed terrace that looks out over all of the medina. Nearby at Rue Bir El Hadjar, once a closed passage belonging to a prince, students sit doing their homework in the doorway of a prestigious music institute. Above, the white facades of the passage gleam like icing on a wedding cake. Binous points out the doorways, explaining that historically the only signs of wealth in the medina were shown on the doors of the traditional houses. Some doorways are framed by stone, others by sculptures. Often the doors are tiny and low, designed to keep houses cool in the summer heat, or to force visitors to bow down as they enter, greeting the occupants. Illustrating her point, Binous invites us into Galerie Medina, a traditional low-doored house that is now an art gallery. As we climb the stairs to the upper level, she explains that the bathrooms of former dars typically sit far from the bedrooms. “Water was historically seen as a link to the underworld,” she says. “People thought the underworld was inhabited by bad spirits, so they didn’t want to sleep anywhere near it.”

Our next stop is Dar El Jeld, Tunisia’s most famous restaurant — and worth popping into just to see the sumptuous dining room with its bronze sculptures, glass chandeliers and ornate vases of orange orchids. And then it’s off into the winding alleys of the souk for a spot of shopping, stopping to buy warm onion, olive and garlic bread from a street vendor as we go.

As the tour winds down, we spot a Tunisian man and his young son strolling past whitewashed walls. Above them, the crimson national flag of Tunisia catches the wind and brushes against a yellow wooden doorway. The man, named Elyes Abbous, smiles at us. “The medina is beautiful,” he says, gesturing to the colorful window frames and at his feet, the tabby kittens asleep on the cobblestones. “As a kid, I used to play soccer between the houses,” he says, reminiscing about a childhood largely spent in the medina. “There’s so much history here, so many stories.”

Related content on AFKTravel:

Four Unmissable Shops in the Tunis Medina

The 8 Incredible UNESCO Sites In Tunisia (And Why You Should Visit Them)

Photo Essay: A Tour Through The Stunning Streets Of Tunis