Lesotho, a sparsely populated mountain kingdom surrounded by South Africa, is the world’s highest country (it has the highest low point, at around 1,400m, in the so-called Lowlands). For most of the 20th century, trading posts were the primary centres of commerce in the country’s high mountains and remote villages. Imagine establishing and running these commercial outposts a century ago, when roads were rare and building materials were transported by donkey; this entailed bravery and hardship on the mountain kingdom’s wild frontiers. Today, driving Lesotho’s pockmarked tarmac roads, gravel chicanes and tortuous mountain passes, such as the God Help Me Pass, is still challenging, but a vast improvement on yesteryear. Which makes it a feasible adventure to visit the numerous trading posts that have been converted into lodges, where guests can appreciate the swashbuckling romance of a bygone era, in the stirring setting of the rugged Drakensberg and Maluti ranges.

The network of trading posts was founded by entrepreneurs, who procured crops, cattle, wool and mohair from the largely rural Basotho population, and sold these commodities into established markets in South Africa. Later, they began selling goods to the Basotho and adding services, such as post offices, animal husbandry, grain milling, fuel and liquor sales, and monthly clinics. The trading posts were, of course, often responsible for creating these demands, by developing links between remote mountain communities and the rest of the world.

When Lesotho, then the British protectorate of Basutoland, gained independence in 1966, the new government banned trade in wool, mohair and animals. This effectively strangled the revenue streams of the trading stations, which educated Basotho resented for encouraging debt-dependency among rural folk. It is true that many traders fought the replacement of mule pack trains with motorised transport in the early 1960s, as it threatened their control over the movement of goods. However, the traders were not colonial stooges, but rather a free-spirited breed who resented the British administrative control and taxes. They generally had a positive relationship with the Basotho villagers, spoke Sesotho, and endured many of the same deprivations.

A famous trader was Mervyn Bosworth Smith, who established Malealea trading post after graduating from Oxford and teaching rugby in Cape Town, diamond prospecting and fighting in the Anglo-Boer War. Stories abound about this larger-than-life character’s achievements and escapades. When riding to play rugby, he tied an alarm clock around his neck, enabling him to doze off and wake at intervals to check his horse was on course. Starting in a tent, he built a store, sheds, and a stone-and-thatch house on the remote plateau, transporting the building materials by ox-wagon – along with a billiards table. The score book in the wood-panelled billiards room became a record of 20th century events, and of the government officials, policemen and travellers who passed through.

Smith died in 1950 and the current owners converted the trading post to Malealea Lodge in the late ‘80s. Two fires destroyed the main house and store over the years, but the site retains a wonderful sense of history. Smith’s pioneering spirit remains in the Gates of Paradise Pass, which he built to bring building supplies, and the bird bath inscribed with ‘anno vic’ (‘year of victory’), celebrating the end of WWII. The lodge offers ‘Lesotho in a nutshell’, through activities such as trekking on Basotho ‘ponies’ (diminutive horses), hiking and village visits, all guided by the local community. Watching the Malealea village choir among thatched rondavels, as sunset tints the Thaba Putsoa Mountains crimson and beers are opened on the stoep, induces a heady feeling of freedom and adventure.

A six-day pony trek from Malealea, or a twisty drive over several mountain passes, is Semonkong Lodge. Semonkong’s name, which means ‘place of smoke,’ comes from Maletsunyane Falls, a misty waterfall crashing 200m into a canyon. The lodge once accommodated staff carrying out stocktakes at the Frasers store – who braved the 20-minute light-aircraft flight from the capital, Maseru. The Frasers chain prospered by selling the Basothos’ beloved patterned blankets, which are still seen over herders’ shoulders. When the Semonkong branch opened in 1938, the building materials arrived by donkey – 1,000 of them. Timber struts, which trailed along the ground to lessen the weight on the animals, were cut 60cm longer than needed, as they would wear down during the journey. The first manager, Jimmy Ashdown, and his wife lived in a two-room mud hut. He readily tore up a floorboard to replace a propeller on the wind-powered battery charger for his radio, which kept him updated with WWII approaching.

Today, Semonkong Lodge offers cosy rondavels with open fireplaces and an English-style pub. Community-run activities include fly-fishing, pub crawls by donkey, and of course abseiling down Maletsunyane Falls – the world’s longest commercially operated, single-drop abseil. Links are still being forged between this corner of the Thaba Putsoa and other places; a recently constructed tar road from here to southern Lesotho has opened a new cross-country route.

Molumong Lodge, in contrast, remains isolated – on the gnarly gravel road between the famous Sani Pass, which climbs over 1,300m from South Africa, and Katse Dam. Surrounded by the Maluti Mountains, the lodge offers self-catering, electricity-free rooms and rondavels, and pony treks to southern Africa’s highest peak, Thabana Ntlenyana (3482 m). A doughty Scotsman, John White-Smith, founded Molumong trading station in 1926, having persuaded the local chief to give him the worst piece of land in the district. Building materials had to be transported by donkey and mule – a four-day trudge up Sani Pass.

White-Smith later bought Good Hope farm at the bottom of the pass in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, where the Sani Pass Hotel now stands. Molumong became a satellite of Good Hope, with mule trains carrying supplies up the pass and grain, wheat, barley, wool and mohair down. The last trader, Gilbert Tsekoa, passed away in 2009, having latterly run a basic shop at Molumong, catering to locals and lodge guests.

Down in the Lowlands, Roma Trading Post sits quietly on the edge of town, near the leafy campus of Lesotho’s only university. The store and guesthouse are run by the fourth generation of Thorns here, descended from John Thorn, who founded the trading post in 1903. Staying in the original sandstone homestead, you might wander out to see blanket-clad horsemen coming to shop, donkeys bringing grain for grinding, or chickens pecking in the garden. The Basotho staff brilliantly complement this old-world charm, offering activities such as visits to the minwane (dinosaur footprints) and Kaycees student bar.

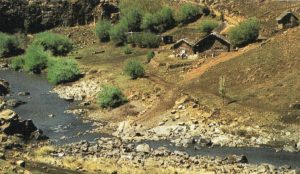

Further up the tar road from Maseru to Semonkong, the Thorns and partners have turned the residential section of Ramabanta Trading Post into a guesthouse. John Thorn built the store, overlooking the Makhaleng River Valley from its clifftop perch, at the invitation of the local chief in 1939. Ramabanta offers a typical mix of mountain views, historical echoes and community-run activities, providing a stepping stone between Roma and Semonkong on multiday pony treks and hikes.